Findings

Theme 1 - Neighbours and Social Glue

Question: What acts as social glue in blocks of flats?

Because most of the research took place during the pandemic, when people had to spend more time than ever before in their homes, relationships with neighbours had a huge impact (whether negative or positive) on the quality of inhabitants’ everyday lives. Some neighbours talked to each other for the first time, they helped with shopping and other tasks, and some also volunteered in the wider community. At the other extreme, some people became even more isolated than before, others became hypersensitive to the behaviour of those around them and tensions were rife; many disputes centred around disobedient noises and smells. This led us to explore what enabled residents to connect with others:

Places that facilitated connections with others were balconies with flowers (as one Barbican resident put it: ‘being able to see other people’s flowers is a point of connection and pleasure’), parks with play- areas for children, coffee stalls, cafes, and libraries (the Barbican library was repeatedly mentioned).

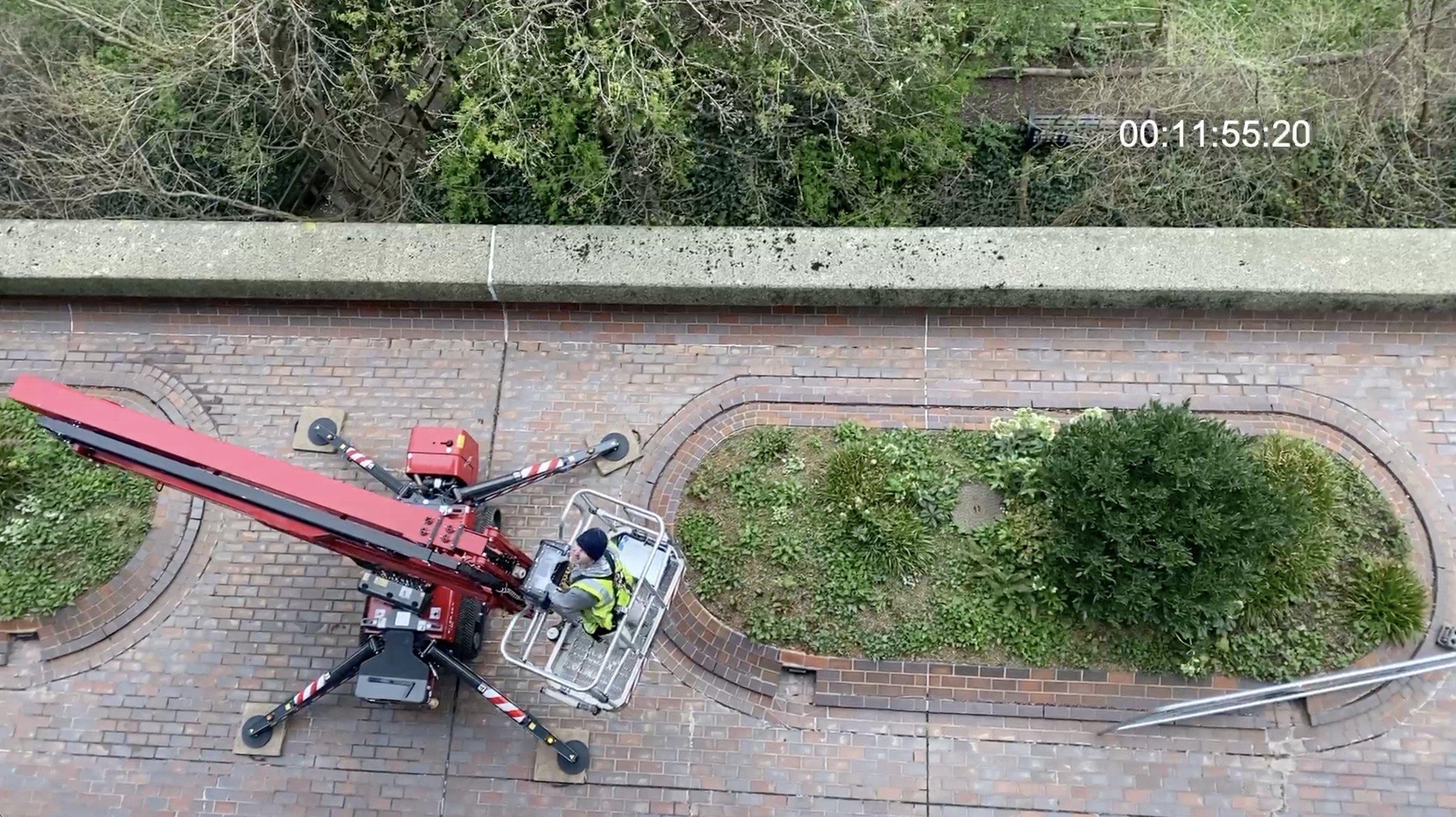

People that provided social glue, especially

for those living on their own, were car park attendants, carers, gardeners, maintenance workers and even local café owners. These individuals provided a listening ear and a social connection that had a positive impact on people’s wellbeing.

Pets were cherished companions. They can both cause tensions with neighbours and act as social glue; whether people took care of each other’s pets when they are away, or, in the case of dogs, they made it easier for people to speak with others while they were out and about. Daniels also observed people feeding animals such as ducks and squirrels in green spaces surrounding their homes, especially during the pandemic. Some were critical of these practices because they also attracted other animals like rats and foxes.

Theme 2: Precarity and Inequality

Question: How do residents experience precarity and inequality on the ground;

what is the impact on their wellbeing?

Heating was a topic that surfaced repeatedly in relation to precarity and inequality. In two of the blocks the heating is switched off between May and October; which is not an ideal situation considering British spring and autumn can be very chilly. While those who could afford it would add extra electric or petrol heaters, in one block inhabitants discovered during the first lockdown that many people, especially the elderly, were sitting at home in the cold. The residents came together and successfully fought the Council to keep the heating on during the pandemic. Another example of precarity but also mutual aid in this block was the foodbank that residents operated in the entrance-hall to the block; people would leave food items – often from the reduced shelf in the local supermarket - for others to pick up.

All the participants whether social tenants, private renters or lease holders were concerned about increasing bills – and this has only gotten worse over the past few months with rise in energy bills as well as the cost of living. Maintenance issues in ageing blocks are unpredictable; especially worry-some are break-downs of large infrastructural elements like lifts, water tanks or boilers. In two blocks tensions erupted between social tenants and lease holders, when communal boilers needed to be replaced and lease holders who were bearing the brunt of the bill questioned whether this work was necessary. More generally residents questioned: ‘why fix what isn’t broken’, referring to the authorities installing new fire doors, kitchens or windows, while the old ones where still in a very good state and actually of better quality than their replacements. Some insinuated that this was due to bureaucracy or even a form of corruption with work being given to friends.

Theme 3: Health and Care

Question: What does it mean to be an ageing (but also ill or disabled) body in an ageing building?

Many inhabitants living in the ageing blocks studied were elderly. Most wanted to stay in their homes and live independently as long as possible. However, because there are no care homes or assisted living accommodation in central London, when people need permanent care they must move away from their local social networks. All praised the support from NHS or private carers, but also the medical infrastructure provided by the NHS for free; devices like special beds, chairs, walkers, wheelchairs, toilet seat, shower chairs and alarms that allows them to live independently for as long as possible. John, a Barbican resident, jokes that Betty needs so much equipment that their living room looks like a hospital.

The design of the flats studied in London does not necessarily account for ageing bodies. Most were maisonettes with stairs over two or three levels. While this is a much-liked feature when people are younger, it becomes a constant worry when they age and one couple in Daniels study moved to a flat without stairs when they were in their seventies for that reason. However, some such as Felicity, who has mobility issues, use walking up and down stairs as their daily exercise to keep them active and healthy. The way many estates are laid out with pedestrian walkways and lifts also enables elderly and disabled people to navigate different routes to go shopping, visits the GP or meet friends in the area.

The UK population is ageing and more people than ever before receive care and help in their homes, but what will social care look like in the future? Daniels study stressed the need to design a variety of housing solutions for the elderly (not only care homes but also assisted living spaces) in locations close to where their active social networks are. These buildings also need to be considered within larger networks of hospitals, hospices, and housing for key staff such as nurses.

Theme 4: Infrastructure, Safety and Security

Question: What makes a place feel like a safe and secure home?

How has the weakening of the Welfare State affected trust in governments?

Most residents worried about the building works going on around their homes. Hotels, offices and new homes were popping up at great speed on the boundaries but also underneath or on top of their estates. (Re-)development projects have a huge impact on people’s everyday lives and, although there was some hope initially that the pandemic would put a stop to these practices, the situation seems to have gotten worse.Mistrust towards local authorities was widespread and participants expressed anxiety about having no control over regeneration plans in their area. Other reoccurring worries were about the decay of the buildings with leaks and fire safety being the most contentious. They felt ignored and patronised with regards to decisions made about their homes; “no one listens or “nothing changes” was a common mantra. Social tenants were as keen as more privileged residents to protect their homes, but the former tend to lack the resources and expertise to challenge decisions made by their Council. This said, during the pandemic some residents were successful in reverting controversial decisions through collective action, i.e., switching the heating off in winter. This resulted in them feeling more confident to question other plans such a major redevelopment that would add 200 homes next to their building.

Another contentious issue, resulting from the authorities outsourcing their welfare responsibilities, is the so-called ‘care in the community’ scheme; whereby people with mental health and other issues are given flats in council estates without much follow-up or medical help. In one block, for example, a man with mental health issues started hording garbage in his flat which led to a health emergency. Alcoholism and drug addiction were other common problems. Residents were also critical of the temporary placement of refugees in their blocks. Because of the fleeting nature of their stay, these inhabitants have little interest in creating relationships with other residents and engaging in activities that encourage feelings of belonging and community. In the Barbican site, empty flats, either second homes or homes bought as investments, were considered problematic for the same reasons. Finally, councils often ignore that those living in blocks